Eco-Econ 101

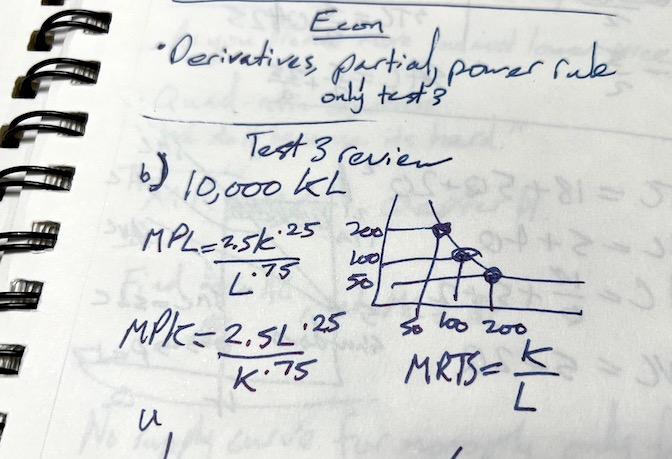

Years ago I was considering going back to school to get a masters in economics. Because my undergrad was in media production my admissions advisor recommended I take a couple lower level micro and macro economics classes to prepare for the program. I was working at the time as an editor and video producer as well as teaching film classes at night (and preparing for my son to arrive). But I put in the work to graph the utility preference curves, the intersection of supply and demand, etc.

I kept waiting for the “real stuff”. For the theory and math to escalate to match the complexity of the real economy as we experience it. The rubble of the economic mess of 2008 was still fresh in my mind. Around that time books like Freakonomics had become popular and Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational captured my attention. I was curious about the real decisions people make even though economists consider them economically “irrational”.

Finally, near the end of these classes I asked one of my professors when we’d cover more realistic scenarios instead of toy models with illusions of mathematical purity and yet little of the richness of reality. He shyly told me the whole department was focused on “traditional” economics with the advanced masters level classes focused on econometrics. He thought maybe one other professor mentioned alternatives, like behavioral economics, in one class. I realized this was not the department I was looking for.

The “traditional” classes taught foundational ideas like “fully rational agents” - people acting 100% in their own self-interest (at all times!) and excellent prediction of the future - which seemed totally contrary to everyone I knew (but maybe I only ever met irrational people). I didn’t have the words or mental models of what I thought might be a more reasonable way to study economics, I was looking to the closest experts to learn, but I didn’t want to pause my career for something so abstract and impractical. I wanted tools to understand, fold in new data, and hopefully predict or manage based on some scientific understanding.

Wandering and learning on my own the last few years has finally landed me on what I was looking for years ago: ecological economics.

The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of ready-made answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.

My ongoing study of complexity pairs well with the systems thinking of folks like Jon Erickson and William Rees, as well as outspoken critics of neoclassical economics like Steve Keen. Keen’s work (best summarized in this podcast interview) ruthlessly, and thoroughly, dismembers the broken assumptions at the core of neoclassical thinking. Erickson’s book, The Progress Illusion, provides a gentler takedown as well as wonderful reminders of hope like Robert Kennedy’s famous speech about the limits of GDP.

... if we judge the United States of America [by our Gross National Product], that counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl.

...

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.

Where I hope all this leads me is a more robust understanding of how the economy actually works framed within the obvious physical limits of our planet.

... anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.